Giclée (zhee-KLAY) is a term coined in 1991 by printmaker Jack Duganne for fine art digital prints made on inkjet printers.[1] The name was originally applied to fine art prints created on a modified Iris printer in a process invented in the late 1980s. It has since been used loosely to mean any fine-art printing, usually archival, printed by inkjet. It is often used by artists, galleries, and print shops to suggest high quality printing, but is an unregulated word with no associated warranty of quality.[2]

Origins

The word giclée was adopted by Jack Duganne around 1990. He was a printmaker working at Nash Editions. He wanted a name for the new type of prints they were producing on a modified Iris printer, a large-format, high-resolution industrial prepress proofing inkjet printer on which the paper receiving the ink is attached to a rotating drum. The printer was adapted for fine-art printing. Duganne wanted a word that would differentiate such prints from regular commercial Iris prints then used as proofs in the commercial printing industry. Giclée is based on the French word gicleur, the French technical term for a jet or a nozzle, and the associated verb gicler (to squirt out). Une giclée (noun) means a spurt of some liquid.[3][4][5] The French verb form gicler means to spray, spout, or squirt. Duganne settled on the noun giclée.[3][6][7]

The History of

Photography

The History of

The Camera

The Physics of

Light

Etching to

Giclée

The History of

Photoshop

The RAW

Image

Photo

Restoration

Etching to Giclée Printing

Etching

Etching is part of the intaglio family.

In pure etching, a metal plate (usually copper, zinc, or steel) is covered with a waxy or acrylic ground. The artist then draws through the ground with a pointed etching needle, exposing the metal. The plate is then etched by dipping it in a bath of etchant (e.g. nitric acid or ferric chloride). The etchant "bites" into the exposed metal, leaving behind lines in the plate. The remaining ground is then cleaned off the plate, and the printing process is then just the same as for engraving.

Although the first dated etching is by Albrecht Dürer in 1515, the process is believed to have been invented by Daniel Hopfer (c.1470–1536) of Augsburg, Germany, who decorated armor in this way, and applied the method to printmaking.[2] Etching soon came to challenge engraving as the most popular printmaking medium. Its great advantage was that, unlike engraving which requires special skill in metalworking, etching is relatively easy to learn for an artist trained in drawing.

Etching prints are generally linear and often contain fine detail and contours. Lines can vary from smooth to sketchy. An etching is opposite of a woodcut in that the raised portions of an etching remain blank while the crevices hold ink.

A non-toxic form of etching that does not involve an acid is Electroetching.

Rembrandt self portrait etching circa 1630

Printmaking

Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. "Traditional printmaking" normally covers only the process of creating prints using a hand processed technique, rather than a photographic reproduction of a visual artwork which would be printed using an electronic machine (a printer); however, there is some cross-over between traditional and digital printmaking, including risograph. Except in the case of monotyping, all printmaking processes have the capacity to produce identical multiples of the same artwork, which is called a print. Each print produced is considered an "original" work of art, and is correctly referred to as an "impression", not a "copy" (that means a different print copying the first, common in early printmaking). However, impressions can vary considerably, whether intentionally or not. Master printmakers are technicians who are capable of printing identical "impressions" by hand. Historically, many printed images were created as a preparatory study, such as a drawing. A print that copies another work of art, especially a painting, is known as a "reproductive print".

Prints are created by transferring ink from a matrix to a sheet of paper or other material, by a variety of techniques. Common types of matrices include: metal etching plates, usually copper or zinc, or polymer plates and other thicker plastic sheets for engraving or etching; stone, aluminum, or polymer for lithography; blocks of wood for woodcuts and wood engravings; and linoleum for linocuts. Screens made of silk or synthetic fabrics are used for the screen printing process. Other types of matrix substrates and related processes are discussed below.

Multiple impressions printed from the same matrix form an edition. Since the late 19th century, artists have generally signed individual impressions from an edition and often number the impressions to form a limited edition; the matrix is then destroyed so that no more prints can be produced. Prints may also be printed in book form, such as illustrated books or artist's books.

Copied from the wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giclée

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, photo by Paul Sescau, 1894.

Lithography

Lithography is a technique invented in 1798 by Alois Senefelder and based on the chemical repulsion of oil and water. A porous surface, normally limestone, is used; the image is drawn on the limestone with a greasy medium. Acid is applied, transferring the grease-protected design to the limestone, leaving the image 'burned' into the surface. Gum arabic, a water-soluble substance, is then applied, sealing the surface of the stone not covered with the drawing medium. The stone is wetted, with water staying only on the surface not covered in grease-based residue of the drawing; the stone is then 'rolled up', meaning oil ink is applied with a roller covering the entire surface; since water repels the oil in the ink, the ink adheres only to the greasy parts, perfectly inking the image. A sheet of dry paper is placed on the surface, and the image is transferred to the paper by the pressure of the printing press. Lithography is known for its ability to capture fine gradations in shading and very small detail.

Photo-lithography captures an image by photographic processes on metal plates; printing is more or less carried out in the same way as stone lithography.

Halftone lithography produces an image that illustrates a gradient-like quality. Mokulito is a form of lithography on wood instead of limestone. It was invented by Seishi Ozaku in the 1970s in Japan and was originally called Mokurito.[4]

Comte Henri Marie Raymond de

Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (24 November 1864 – 9 September 1901) was a French painter, printmaker, draughtsman, caricaturist and illustrator whose immersion in the colorful and theatrical life of Paris in the late 19th century allowed him to produce a collection of enticing, elegant, and provocative images of the sometimes decadent affairs of those times.

Born into the aristocracy, Toulouse-Lautrec broke both his legs around the time of his adolescence and, due to an unknown medical condition, was very short as an adult due to his undersized legs. In addition to his alcoholism, he developed an affinity for brothels and prostitutes that directed the subject matter for many of his works recording many details of the late-19th-century bohemian lifestyle in Paris.

In a 2005 auction at Christie's auction house, La Blanchisseuse, his early painting of a young laundress, sold for US$22.4 million and set a new record for the artist for a price at auction.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_de_Toulouse-Lautrec

Toulouse Lautrec, Moulin Rouge, La_Goulue 1861

Monotype

Monotyping is a type of printmaking made by drawing or painting on a smooth, non-absorbent surface. The surface, or matrix, was historically a copper etching plate, but in contemporary work it can vary from zinc or glass to acrylic glass. The image is then transferred onto a sheet of paper by pressing the two together, usually using a printing-press. Monotypes can also be created by inking an entire surface and then, using brushes or rags, removing ink to create a subtractive image, e.g. creating lights from a field of opaque color. The inks used may be oil based or water based. With oil based inks, the paper may be dry, in which case the image has more contrast, or the paper may be damp, in which case the image has a 10 percent greater range of tones.

Unlike monoprinting, monotyping produces a unique print, or monotype, because most of the ink is removed during the initial pressing. Although subsequent reprintings are sometimes possible, they differ greatly from the first print and are generally considered inferior. A second print from the original plate is called a "ghost print" or "cognate". Stencils, watercolor, solvents, brushes, and other tools are often used to embellish a monotype print. Monotypes are often spontaneously executed and with no preliminary sketch.

Monotypes are the most painterly method among the printmaking techniques, a unique print that is essentially a printed painting. The principal characteristic of this medium is found in its spontaneity and its combination of printmaking, painting, and drawing media.[6]

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (UK: /ˈɡoʊɡæ̃/, US: /ɡoʊˈɡæ̃/; French: [ø.ʒɛn ɑ̃.ʁi pɔl ɡo.ɡɛ̃]; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French Post-Impressionist artist. Unappreciated until after his death, Gauguin is now recognized for his experimental use of color and Synthetist style that were distinct from Impressionism. Toward the end of his life, he spent ten years in French Polynesia. The paintings from this time depict people or landscapes from that region.

His work was influential on the French avant-garde and many modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, and he is well known for his relationship with Vincent and Theo van Gogh.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Gauguin

Paul Gauguin, Arearea no Varua Ino (Words of the Devil),

watercolor monotype on Japan paper mounted on cardboard, 1894

Woodcut

Woodcut, a type of relief print, is the earliest printmaking technique. It was probably first developed as a means of printing patterns on cloth, and by the 5th century was used in China for printing text and images on paper.[citation needed] Woodcuts of images on paper developed around 1400 in Japan, and slightly later in Europe.[citation needed] These are the two areas where woodcut has been most extensively used purely as a process for making images without text.[citation needed]

Woodcuts of Stanislaw Raczynski (1903–1982)

The artist either draws a design directly on a plank of wood, or transfers an drawing done on paper to a plank of wood. Traditionally, the artist then handed the work to a technician, who then uses sharp carving tools to carve away the parts of the block that will not receive ink.[citation needed] In the Western tradition, the surface of the block is then inked with the use of a brayer; however in the Japanese tradition, woodblocks were inked with a brush.[1] Then a sheet of paper, perhaps slightly damp, is placed over the block. The block is then rubbed with a baren or spoon, or is run through a printing press. If the print is in color, separate blocks can be used for each color, or a technique called reduction printing can be used.

Reduction printing is a name used to describe the process of using one block to print several layers of color on one print. Both woodcuts and linocuts can employ reduction printing. This usually involves cutting a small amount of the block away, and then printing the block many times over on different sheets before washing the block, cutting more away and printing the next color on top. This allows the previous color to show through. This process can be repeated many times over. The advantages of this process is that only one block is needed, and that different components of an intricate design will line up perfectly. The disadvantage is that once the artist moves on to the next layer, no more prints can be made.

Another variation of woodcut printmaking is the cukil technique, made famous by the Taring Padi underground community in Java, Indonesia. Taring Padi Posters usually resemble intricately printed cartoon posters embedded with political messages. Images—usually resembling a visually complex scenario—are carved unto a wooden surface called cukilan, then smothered with printer's ink before pressing it unto media such as paper or canvas.

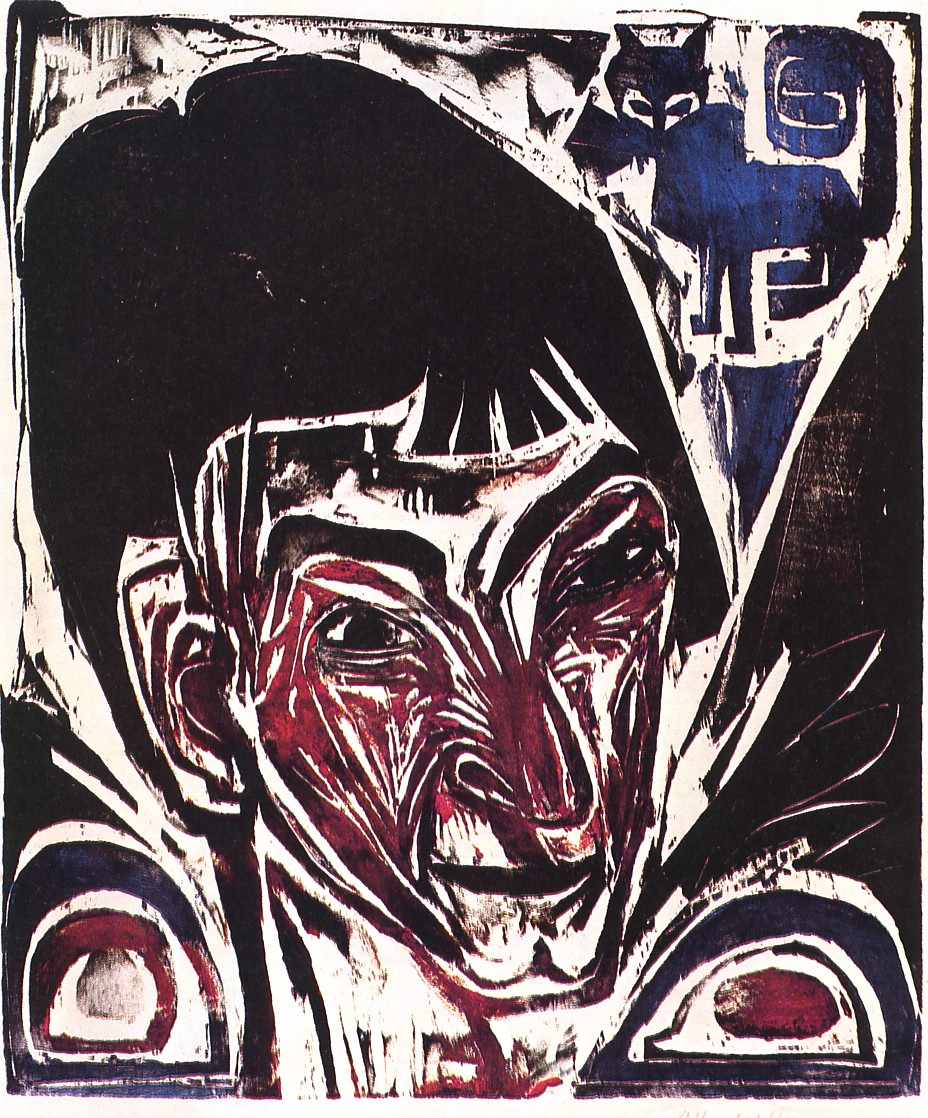

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Portrait of Otto Müller, 1915

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (6 May 1880 – 15 June 1938) was a German expressionist painter and printmaker and one of the founders of the artists group Die Brücke or "The Bridge", a key group leading to the foundation of Expressionism in 20th-century art. His work was branded as "degenerate" by the Nazis in 1933, and in 1937 more than 600 of his works were sold or destroyed.[1]

Katsushika Hokusai The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 1829/1833, color woodcut,

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾 北斎, c. 31 October 1760 – 10 May 1849), known simply as Hokusai, was a Japanese artist, ukiyo-e painter and printmaker of the Edo period.[1] Hokusai is best known for the woodblock print series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji which includes the internationally iconic print The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

Hokusai created the monumental Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji both as a response to a domestic travel boom in Japan and as part of a personal obsession with Mount Fuji.[2] It was this series, specifically The Great Wave off Kanagawa and Fine Wind, Clear Morning, that secured his fame both in Japan and overseas. While Hokusai's work prior to this series is certainly important, it was not until this series that he gained broad recognition.[3]

Hokusai's work transformed the ukiyo-e artform from a style of portraiture largely focused on courtesans and actors into a much broader style of art that focused on landscapes, plants, and animals. Hokusai worked in various fields besides woodblock prints, such as painting and producing designs for book illustrations, including his own educational Hokusai Manga, which consists of thousands of images of every subject imaginable over fifteen volumes. Starting as a young child, he continued working and improving his style until his death, aged 88. In a long and successful career, he produced over 30,000 paintings, sketches, woodblock prints, and images for picture books in total. Innovative in his compositions and exceptional in his drawing technique, Hokusai is considered one of the greatest masters in the history of art.

Engraving

The process was developed in Germany in the 1430s from the engraving used by goldsmiths to decorate metalwork. Engravers use a hardened steel tool called a burin to cut the design into the surface of a metal plate, traditionally made of copper. Engraving using a burin is generally a difficult skill to learn.

Gravers come in a variety of shapes and sizes that yield different line types. The burin produces a unique and recognizable quality of line that is characterized by its steady, deliberate appearance and clean edges. Other tools such as mezzotint rockers, roulettes (a tool with a fine-toothed wheel) and burnishers (a tool used for making an object smooth or shiny by rubbing) are used for texturing effects.

To make a print, the engraved plate is inked all over, then the ink is wiped off the surface, leaving only ink in the engraved lines. The plate is then put through a high-pressure printing press together with a sheet of paper (often moistened to soften it). The paper picks up the ink from the engraved lines, making a print. The process can be repeated many times; typically several hundred impressions (copies) could be printed before the printing plate shows much sign of wear, except when drypoint, which gives much shallower lines, is used.

In the 20th century, true engraving was revived as a serious art form by artists including Stanley William Hayter whose Atelier 17 in Paris and New York City became the magnet for such artists as Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Mauricio Lasansky and Joan Miró.

Albrecht Dürer was a German painter, printmaker, and theorist of the German Renaissance. Born in Nuremberg, Dürer established his reputation and influence across Europe in his twenties due to his high-quality woodcut prints. He was in contact with the major Italian artists of his time, including Raphael, Giovanni Bellini, and Leonardo da Vinci, and from 1512 was patronized by Emperor Maximilian I.

Melencolia I, 1514 engraving by Albrecht Dürer, one of the most important printmakers.

Mezzotint

Mezzotint is a monochrome printmaking process of the intaglio family.[2] It was the first printing process that yielded half-tones without using line- or dot-based techniques like hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. Mezzotint achieves tonality by roughening a metal plate with thousands of little dots made by a metal tool with small teeth, called a "rocker". In printing, the tiny pits in the plate retain the ink when the face of the plate is wiped clean. This technique can achieve a high level of quality and richness in the print.

Mezzotint is often combined with other intaglio techniques, usually etching and engraving. The process was especially widely used in England from the eighteenth century, to reproduce portraits and other paintings. It was somewhat in competition with the other main tonal technique of the day, aquatint. Since the mid-nineteenth century it has been relatively little used, as lithography and other techniques produced comparable results more easily. Robert Kipniss and Peter Ilsted are two notable 20th-century exponents of the technique; M. C. Escher also made eight mezzotints.

The mezzotint printmaking method was invented by the German amateur artist Ludwig von Siegen (1609–c. 1680). His earliest mezzotint print dates to 1642 and is a portrait of Countess Amalie Elisabeth of Hanau-Münzenberg. This was made by working from light to dark. The rocker seems to have been invented by Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a famous cavalry commander in the English Civil War, who was the next to use the process, and took it to England. Sir Peter Lely saw the potential for using it to publicise his portraits, and encouraged a number of Dutch printmakers to come to England. Godfrey Kneller worked closely with John Smith, who is said to have lived in his house for a period; he created about 500 mezzotints, some 300 copies of portrait paintings.

John Smith (c. 1652 – c. 1742) was an English mezzotint engraver and print seller. Closely associated with the portrait painter Godfrey Kneller, Smith was one of leading exponents of the mezzotint medium during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and was regarded among first English-born artists to receive international recognition, along the younger painter William Hogarth.

From the wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Printmaking

Saint Agnes, mezzotint by John Smith usually thought to be a portrait of his daughter, Catherine Voss. 1716